Dry Fly Innovations - by Craig Schuhmann

“Those of us who will not in any circumstances cast except over rising fish are sometimes called ultra-purists and those who occasionally will try to tempt a fish in position but not actually rising are termed purists... and I would urge every dry fly fisher to follow the example of these purists and ultra-purists.”

— Frederic Halford

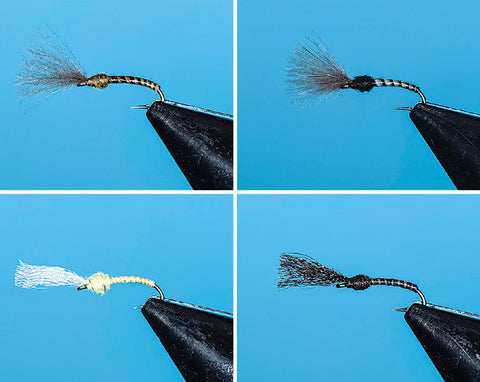

A selection of size #20-22 Colored Emergers.

Ten years ago, Nat Brumley had a wild idea. This retired school teacher of thirty years decided to start a business devoted to the sale of dry flies. But this wasn’t just another online shop selling imported patterns, Nate had a much bigger mission in mind. He believed that if he had the right blend of education, customer service and well-designed flies, he could entice anglers with a promise: the ability to harness the power of the dry fly and find fishing success unimaginable to most anglers. Of course, this was a bold claim and an even bolder decision to base a business on, but Nate was confident in the face of doubters and felt the time was right for reevaluating and reimagining our approach to fly fishing.

Ten years later, Dry Fly Innovations, based in Boise, Idaho is still going strong. And Nate is just as evangelistic about his mission today as he was 10 years ago. This apostle of the dry fly claims to have never, in 50-plus years of fly fishing, caught a fish on anything but a floating fly. A quick survey of this on-line business will reveal a combination of tools that he credits for his success: a catalogue of original dry flies, a few specific tying materials, two self-published books, instructional DVD’s, extensive fishing reports and a comprehensive subscriber-only blog. One will notice that Nate’s flies have mostly unfamiliar names: Colored Emergers, Humpilators, Adam’s Caddis, Searchers, Emperor Caddis, Bare-belly Caddis, Converters, Twofer Mayflies, Adam’s Stimulators, Black and Gold Stimulators and PMD Stimulators. Even the familiar flies such as comparaduns, cripples and no-hackles seemed to have a specific twist unique to Nate’s vision of what a fly should be.

Nate Brumly on the South Fork of the Boise River with a 26” rainbow caught on a size #20 BWO Twofer.

My introduction to Dry Fly Innovations occurred last fall when a friend and I were planning to fish the Owyhee in Eastern Oregon. An angler from that area told us about a skating technique using one of Nate’s flies, the black and gold Stimulator. Rather than tie a couple dozen of this oddly colored fly from a photo, we each ordered a dozen in several sizes and set off to the Owyhee.

The fishing that weekend was not great no matter what we used, but the flies we ordered were intriguing and did generate a few strikes. In addition to the Black and Gold, I also ordered a few other patterns such as the Searcher and several Colored Emergers accompanied by a few suggestions from Nate as to their use. Later, Nate sent me one of his books and gave me access to his fishing blog which is a subscriber only.

“If I can always find the solution with a dry fly, why would I choose anything else?” Nate poses this question to me during one of our phone conversations, after I ask him if he has ever considered or been tempted to use a nymph, streamer or wet fly. I then ask if he considers himself a dry fly purist, knowing this can be a negative phrase among fly anglers. There was no hesitation from Nate, “No, and I’m not even sure what ‘dry fly purist’ even means. I started fishing dry flies as a means of subsistence in my youth and never had a reason to use anything else. I didn’t learn about nymphs until I was 19-years old. When I speak at shows or to other anglers and tell them my story, I can see the skeptical look in their eye. I have met those who claim to be dry fly purists, but I don’t seem to share their values or motivations. I’m not fishing dry flies to impress anybody or because I think it’s a higher form of fly fishing. Neither do I judge other angler’s methods. I fish dry flies because that’s the way I learned to fish and I never had the need for any other type of fly.” Nate says the joy of fishing a dry fly is seeing the fish ‘eye to eye’ as they comes up for the fly, and if deprived of that experience, he doubts if he’d still be fly fishing.

- BWO Convertable (left)

- Baetis Green Tanalizer (middle)

- Black Gold Stimulator (right)

As for the statistic that most fish feed 90% of the time under the surface? This fact doesn’t even phase Nate or get him to pause and consider a sunk fly. As far as Nate is concerned, the studies and stomach samples which prove this statistic do not specify when those sunk flies are eaten. It’s Nate’s suspicion that a lot of those insects are eaten in the process of emerging—mature nymphs or fully emerged adults moving to the surface using their adaptive methods to break through the meniscus. Nate says, “Rise forms are often very subtle and most go completely unnoticed by anglers because they just aren’t looking for them. I have the feeling that a lot of the studies are, in fact, talking about emerging insects on or near the surface film. I fish dry flies that do that.” Just in case you are wondering, Nate defines a dry fly as any fly with a protruding feature above the surface of the water.

Nate elaborates on his dry fly fishing experience with an anthropology of sorts about the way we have developed as anglers: “American anglers learn to fly fish by graduating from dry flies to nymphs and streamers. Most anglers catch their first fish on a dry fly, but when conditions get tough or there’s no hatch and bigger fish are desired, we are taught dry flies won’t work, so we switch to nymphs, wet flies and streamers.” Nate uses an interesting proverbial image here to capture the moment when an angler replaces a dry fly with a sunk fly: ‘sniping off the dry fly’. Nate explains, “Knowledge of these other techniques is fine, and I don’t disparage their use, I just never ‘sniped off the dry fly’”. As I listen to Nate, I get the feeling that there is a tragic element to his characterization, resulting from the loss of innocence in pursuit of a goal now measured quantitatively rather than qualitatively. If it’s true that Nate is an example of someone who stuck with the dry fly and walked through all the problems in order to let the dry fly experience go on, then he may have something new to say. At least, that’s where I got interested. In other words, Nate says, “Fly fishing cannot become mundane. I need my wits challenged. I’ve caught a ton of fish in my lifetime, so it’s not about catching fish anymore, it’s about catching fish in the face of the challenges and problems they present. Because I’ve stuck with the dry fly, those challenges have been great—vast, even. But no other way will do and if a fish can’t be caught on a dry fly, then I go home fishless or find another piece of water.”

- Brown Hoagie’s Cripple (left)

- Caddidge® - Olive Brown (middle)

- Pink No-Hackle (right)

I’ve heard similar fishing philosophy from other anglers, especially those from older generations who never learned or adjusted to using bead-heads, strike indicators, synthetic materials, and today’s specialized equipment. While their criticism of these techniques can be an affront to those of us who grew up using these methods, their point is well taken. They fish in the way they want to catch fish, not any way that catches fish. There is a qualitative difference between these two ideas which seems to generate a healthy discussion around fly fishing in general. If, as Nate argues, and most of us would agree, dry fly fishing is the most pleasurable way to catch fish, then the question about why we would use anything else raises an interesting challenge.

Nate follows up his characterizations about the loss of the original dry fly experience, “Most American anglers developed along a similar trajectory by rejecting the dry fly except in those very obvious times of surface feeding, and hunt for the biggest fish with nymphs and streamers. I’m always hunting for the biggest fish in the drink.” You may think of Nate as simple angler catching mostly few and small fish only during certain times of the year. According to Nate, and documented in his notebooks, books, and blogs dating back many years, nothing could be further from the truth. Nate continues, “Those of us who have stuck with the dry fly, and there aren’t many, have discovered a hidden world of fly fishing most anglers never get to see.”

Nate and I begin to delve into some of the nuanced differences experienced by a pure dry fly angler (a phrase I will use instead of dry fly purist) and the technical use of dry flies. “A dry fly angler has to be a hunter, with sharp perceptive abilities and the strength to move over a lot of water to find those perfect opportunities. I call it ‘running in slow motion’—you’re moving fast and at the same time observing the minutest of details for any detection of trout. My goal is the biggest fish in the river and to do that consistently with a dry fly, through every season and in all kinds of conditions, you have to understand big fish.”

Nate explained to me his thoughts about big fish and why so few anglers catch them on dry flies. “Big fish are in the cockpit and they are very smart. They see everything and are deeply connected to their environment in ways we don’t completely understand. Acknowledgement and respect for this fact is the first requirement for catching the biggest fish in the river. Approaching big fish and choosing the right fly requires absolute respect for their sensitivity. Most big fish opportunities are lost without the angler even knowing it. Compound this with the need for proper fly selection, leader and tippet choices and presentation, and the dry fly angler has their work cut out for them.”

Nate also understands the limitations of the dry fly: “High, off color water is a killer; you might as well go home or choose a different body of water. Fish are far more interested in eating all the worms, grubs and other meaty food forms rolling down the bottom of the river.”

Another limitation, according to Nate, is experience. “Experience is a great teacher, but you need a lot of experiences over many seasons to develop your skills. To avoid frustration, combine your fishing with good education. This way, when you are on the river you can draw from your learning to help solve certain fishing problems related to catching big fish.” Nate mentions how to conquer some of these fishing problems by paying attention to what he calls, ‘the enormous importance of the tiny details’, which includes proper selection and use of equipment, fly prep, identifying various rise forms, understand where and how fish live in a river or lake, understanding presentation and which fly to use over a big fish.

I ask Nate to tell me his favorite or most productive fly. “I don’t have a favorite fly. I use the fly that best matches the conditions of the hatch and what the fish prefer. During a hatch, insects are always evolving and you don’t want to get married to fishing a particular insect stage when the fish may be looking for something else. Changes in the field of food will, through observation, dictate which fly to use. Basically I have two kinds of flies: searchers and articulated flies” (Nate uses the word ‘articulated’ here to describe a fly which closely resembles the actual insect; it articulates all the features big fish are looking for). “Take my colored emerger, tantalizer or cripple; all articulated flies. These flies are designed to appeal to big fish by the way they ‘posture’ in the water—their angle of submersion. The tails of the colored emergers and cripples must suspend straight down (some at a forty-five degree angle) with only the top portion of the fly, or the wing, suspended above the water. At certain points within a hatch, big fish are looking for insects in a certain posture, particularly when they are in close proximity to the fish; anything lacking this posture gets passed up by the biggest fish. It is these tiny details, along with size, shape and color, which make the difference to a big smart fish—the one in the cockpit.”

I don’t recall Nate using the phrases ‘match-the-hatch’ or ‘selectivity’ in our conversation, and maybe that’s a good thing. Because even though I knew what he was talking about, I didn’t feel the weight of the dogma that accompanies those discussions. I think back to all the great flies tied in the match-the-hatch tradition by such well-studied anglers as Bob Quigley, André Puyans, and Swisher and Richards. I ask Nate if he had any influences in his tying or ideas. “Not really, I haven’t read any books nor am I very familiar with the tiers you mentioned. Everything I’ve done is rooted in my experience.”

The searcher patterns mentioned above are just what they sound like, flies to use when there is no hatch, and comprise the second approach to Nate’s fishing. “My fly fishing breaks down this way: I’m either fishing a hatch or I’m fishing holding water; I’m either fishing to rising fish or trying to make a fish rise. Deliver the right dry fly to where fish live, regardless of the season, and they will eat it. The searcher patterns are for the latter, the articulated flies are for the former.”

I asked Nate about his approach to fly design and testing since most of the flies he sells are his own creations. Nate tells me, “First, does the fly have success for the type of water it is designed for? Flies designed for slick surfaces need to work on slick surfaces. Is it tied on the right hook? Does the hook have the right balancing point to allow it to tip up and yet remain supported in the surface film with the wing? These and a lot of other considerations, such as right material, color, shape and size, go into testing both by myself and a select group of anglers that I know are very good dry fly anglers. Overall, it takes about two years of testing per fly.”

I asked Nate how he gets his flies tied. “A few of the larger flies such as the Stimulators are tied overseas. It’s really hard to find tiers willing to tie big, standard dry flies. All the specialized articulated flies are tied by a group of nine American tiers. It’s amazing how many flies a good tier can crank out in a day, 7- to 8- dozen is no problem. One such tier is Janet Schimpf, a brilliant tier of emerging bugs. Her work on our Drake, Hatching, Tantalizer, and Adams Caddis patterns are nothings short of remarkable.”

Janet Schimpf, one of Nate’s star tiers, at the vice.

This brings us to Nate’s business, Dry Fly Innovations, which really markets a solution-based approach to fishing dry flies. As a former teacher, Nate has designed a multi-layered, multi-sensory educational system which includes flies, books and videos, fly tying demonstrations, a subscription blog and fishing reports. All these elements support and encourage anglers who want to be successful with the dry fly. The cornerstone of his business is selling dry flies and if that’s all you ever bought from Nate, he would be fine with that. “But if you’re looking of more,” Nate says, “we offer a whole world of knowledge. My business approach has been three pronged: education, great dry flies and even better customer support.”

The propensity of successful anglers to want to systematize what they have learned and reduce it to a set of principles is inherent to our sport. Many of the great anglers have done it. Some of these systems have contributed greatly to our collective fly fishing knowledge, in part or whole, and some are far too nuanced and complicated to be useful to anyone other than their originator. Nate Brumley’s system is an interesting one if for no other reason than it challenges us to consider what fishing might be like if we had never ‘sniped off the dry fly’.

Let’s face it, dry fly fishing is tough for those anglers who are not practiced. There are similarities to indicator fishing: drag free drifts, mends, and presentation techniques, but the similarities end there. Targeting a rising fish, keeping the fly afloat and drag free, setting up the drift to reach the fish, timing the rises, properly identifying a hatch, casting and overcoming the adrenalin rush which can cause everything to go to hell in seconds—these are the challenges. Many of the clients I guide, some experienced anglers, have never fished a dry fly because it hasn’t been encouraged. As a guide who often relies on sunk flies to get clients into fish, Nates ideas certainly present a huge disruption and challenge to my way of fishing, and I’m not certain I’m ready for it, but I’m intrigued nonetheless. I cannot argue with the fact that dry fly fishing is the most satisfying way to catch a fish. On this point, I think Nate Brumley and our fly fishing tradition has a stake, so I ask myself, as an angler and guide, what kind of stakeholder I want to be both to myself and my clients?

TYING THE

FLAV SEARCHER

- Thread: Olive Dun Unithread

- Hook: 1260 Daiichi #16 and #14

- Tail: Elk hair dyed dark dun

- Abdomen: Nature’s Spirit BWO Turkey biot

- Wing: Elk hair dyed dark dun

- Dub: Olive Brown Superfine

Step 1: Start the thread at a point that marks the front of the abdomen and the back of the thorax.

Step 2: Tie in the tail and flare it with the final thread wrap by lifting and cinching.

Step 3: Attach the biot at the base of the tail and lay a layer of Krazy Glue along the abdomen.

Step 4: Wrap the biot to the back of the thorax.

Step 5: Mount the wing in tightly with a least 12 turns of thread.

Step 6: Apply a fairly long section of dub to the thread. Pull the wing toward the eye and tightly wrap 3 turns of dub behind the wing. The wing should now be straight up. Advance the dub in front of the wing and snap in a small tight ball of dub in front of the wing.

At this point you must separate the clipped ends of elk hair into legs. Pull 10 to 12 hair butts from each side and trim all hair remaining in the middle.

Step 7: The underside of the bug should look like this.

top view

Step 8: Finish the tie by pulling back the legs and dubbing the rest of the thorax. Make sure the dub is tight against the front of the legs. Snap in a tapered head and tie off under the eye.

We tie the Searcher pattern in multiple colors: Black, Brown, Callibaetis, Flav, Gray, Mahogany, Pink, and PMD. By design this fly is not often used over feeding fish. It’s most effective when served to holding water out of the hatch with the objective of luring a fish up to eat. Thus as its name implies, it’s an attractor or SEARCHER pattern.

There is a strategy used when this bug is employed. Match the color of the most prevalent mayfly on the river to the appropriately colored Searcher. The color is the trigger and you’ll often find fish coming blindly to the right colored Searcher.